ENG 411

Abolition: Then and Now

Introduction

This exhibition is centered on the theme of abolition. It is meant to illustrate the historical and conceptual relationships between the abolitionist movement in the 19th century and the one that exists today through the prism of the writings and experiences of Frederick Douglass and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Through photographs, research from historical archives, and engagement with theory, each student has sought to reflect on these topics from a distinct angle. Taken together, the contributions attempt to point the way forward in the struggle for racial equality and universal liberation by encouraging us to take history seriously, learn from the insights of those who preceded us, and appreciate the unity of thinking and doing.

Ruby Bridges, then six years old, had to be escorted to and from school by U.S. Marshals just to be able to learn with White students. (1960)

Frederick Douglass was the most photographed American of the nineteenth century. (c. 1870)

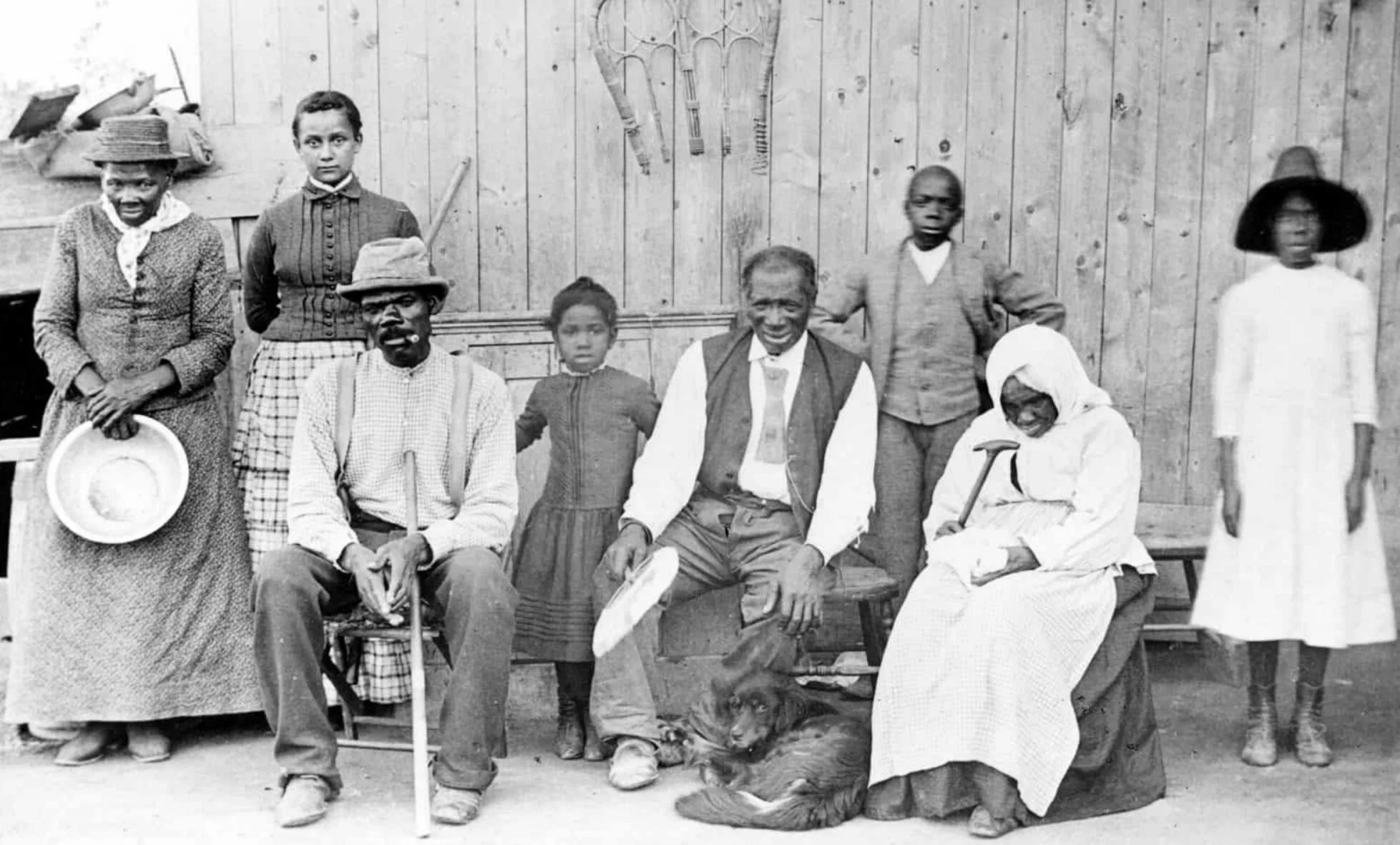

To the far left is abolitionist, Harriet Tubman, pictured with former enslaved persons she helped escort to freedom. (c. 1885)

This is a picture from the Tulsa Race Massacre. Mt. Zion Church was burned down by White rioters. (1921)

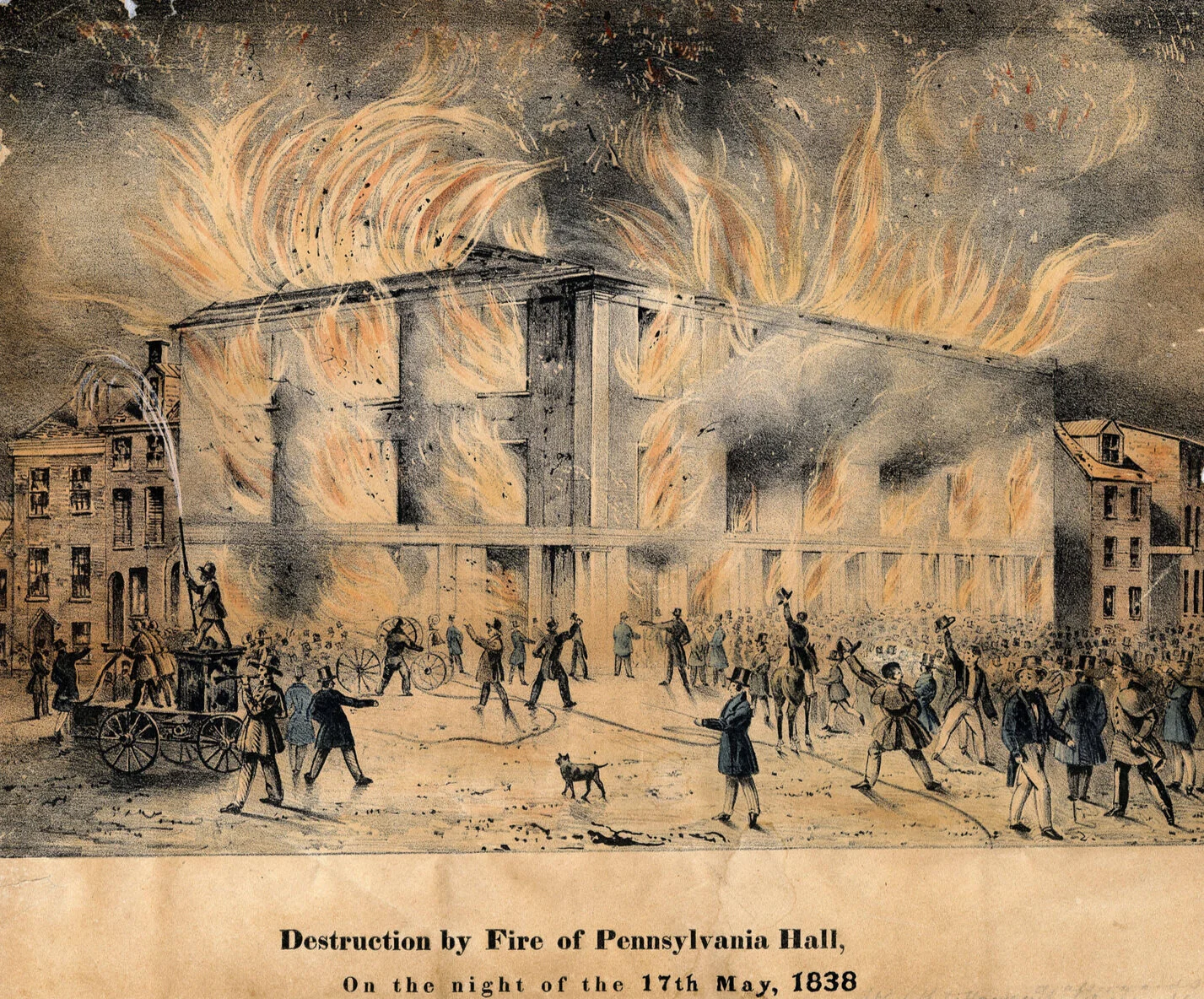

This image is a recreation of the burning of Pennsylvania Hall after an anti-abolitionist mob set it on fire. (1838)

Following a protest for the killing of Michael Brown, a woman kneels on the concrete with her arms outstretched, surrounded by fire and tear gas. (2014)

The Birmingham Fire Department uses powerful hoses, specifically designed to fight fires, to spray human beings exercising their right to protest. (1963)

Ieshia Evans stands boldly still as two officers rush to detain her following a protest for the killing of Alton Sterling. (2016)

The Importance of Photography in Abolition

By: Iliyah Coles

Photography has played a major role in the abolition movement, both then and now. Photographers within the movement have used and continue to use the medium to document various peoples in life’s tragedies and successes. Frederick Douglass spoke about the art of photography in numerous speeches and essays. In this essay, I will discuss a couple of those speeches and relate them to photography in both the Civil Rights Era and the current Black Lives Matter movement. The goal of this piece is to express that photography’s greatest role perhaps is to humanize the lives systemic racism often desensitizes.

Luke Willis Thompson, "Autoportrait," 2017

Sanford Biggers, “Laocoön (Fatal Bert),” 2015

William Blake, “Flagellation of a Female Samboe Slave,” 1796

British Anti-Slavery Medallion, “Am I not a Man and a Brother?” 1787

Hank Willis Thomas, "Thirteen Thousand, Four Hundred and Twentynine" Stars for the victims in the United States in 2015

David Jackson, "Emmett Till," 1955

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (I AM A MAN), 1988

Ti-Rock Moore, "Confronting Truths: Wake Up!" 2015

Ameya Okamoto, Untitled (Portrait of Breonna Taylor), 2020

Xena Goldman, Greta McLain, and Cadex Herrera, "George Floyd Mural at Cup Foods," 2020

(Re)Picturing Black Life in the Face of Death

Text by Cammie Lee

Images, in all their various mediums, are portals into the past and tapestries upon which we project our present desires. Hardly just objects of decorous utility, they move people to act in extraordinary ways. In the fight for abolition, images have united people in shared passion and emotion, providing sites of healing and collective mourning. Yet they may also agitate wounds and deal further injury to those already hurting. In the words that follow, I examine three attempts to visually document a single event in history, detailing impact, public response, and the poetry of the images themselves.Background Image: The Lynching Site of Leo Frank, Marietta, Ga., 1915 by Oliver Clasper. Featured in the photo series “The Spaces We Inherit” from 2018

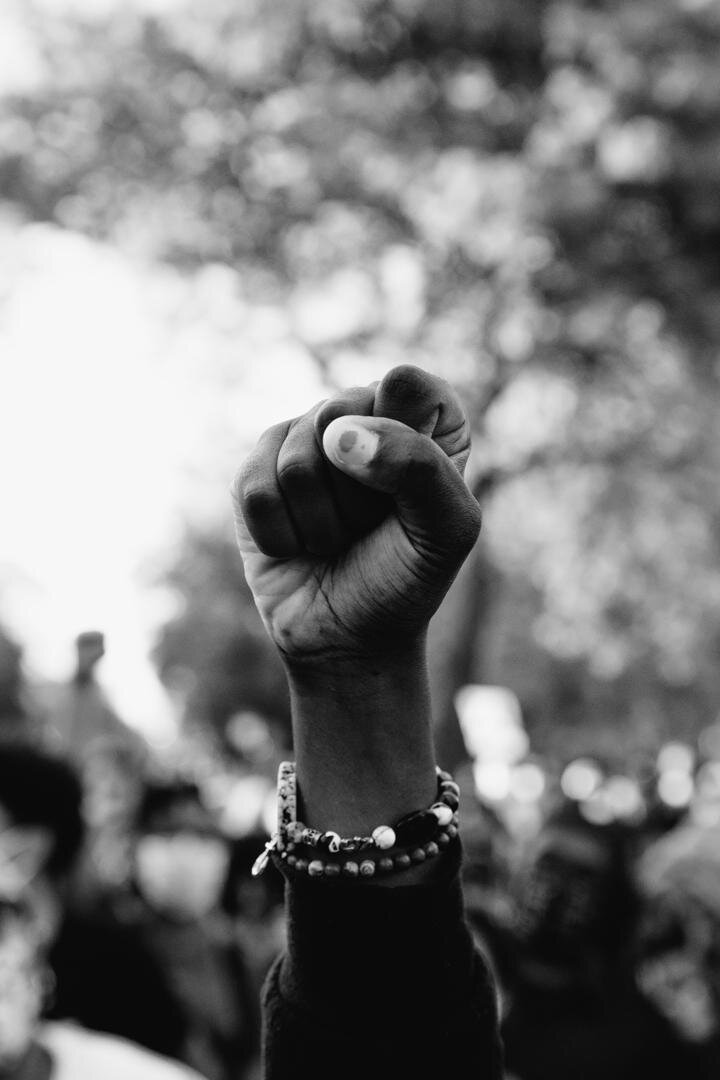

A Black Lives Matter protestor in Minneapolis, Kerem Yucel/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images (c. 2020) Keeanga Yamahatta-Taylor contextualizes the rise of protests and attributes it to the failure of America to protect its Black citizens.

Black Lives Matter protestors march through Portland, Oregon. (c. 2020) A handful of Black Lives Matter protestors have been labeled "domestic terrorists."

The Circus on SHOWTIME, "Joe Biden and Kamala Harris at their first campaign event since the announcement of her selection as VP candidate," YouTube, CC BY-3.0 (c. 2020). Cherrell Brown argues that abolitionist work must continue beyond that of the presidential election.

A mural of Breonna Taylor by Sarahmirk, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-4.0 (c. 2020) Mariama Kaba and Andrea Ritchie assert that the justice Breonna Taylor deserves exceeds what is currently being proposed.

Close up of abolitionist Frederick by Buaidh on Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-4.0, (c. 1856). Many of Frederick Douglass' works can be comparatively analyzed with current abolitionist writers.

A protester holds their hands up in front of a police car in Ferguson, Missouri, on November 25, 2014. Jewel Samad/AFP via Getty Images. Protestors and activists have become symbolic of "woke" ideology.

Old American Congressional Church (c. 2018). Frederick Douglass condemns American churches for their complicity in the perpetuation of slavery in "Abolitionists of Western New York, Awake!"

Fibonacci Blue, "Protest against police violence - Justice for George Floyd, May 26, 2020 11," Flickr.com, CC BY-2.0, (c. 2020) Protests can be seen as avenues for contemporary Black Americans to achieve their own abolition.

TradingCardsNPS, "The North Star," Flickr.com, CC BY-2.0, (c. 2012). Douglass published many of his abolitionist thoughts in his publication, The North Star. These writings can be read in comparison with current writings by abolitionists in Black owned media publishers, like Essence Magazine.

A Comparative Analysis of Historic and Contemporary Writings to Understand Abolition in the Present Day

By: Auhjanae McGee

Abolition is a complex concept. As systemic racism evolves, Black people are still trying to understand how they can conceptualize their own abolition, and they are often met with backlash. Contemporary black writers have published their thoughts on what they believe abolition looks like. And if you look at the writings of Frederick Douglass, you will see striking parallels. Reading contemporary writers in comparison with Douglass demonstrates how abolitionist ideas persist throughout history and abolitionist thought may not be as radical as originally believed.

Background Image: Fibonacci Blue, “Juneteenth reparations rally to demand reparations from the United States government,” Flickr.com, CC BY-2.0 (2020).

Archives of History: Dominant Media and Understandings of the Call to ‘Defund the Police’

by Isabel Lewis

In studying Douglass and Emerson, we discussed how media does not only create a record of events, but is a force in shaping their meaning and historical significance. Throughout the course of U.S history dominant media has worked against the cause of prison abolition by supporting the narrative of black criminality, while simultaneously downplaying the brutality of our own American institutions. Whether it be the intentional and rare use of color in capturing the Civil Rights Movement, to modern fixations on looting and rioting, rather than the call for police reform, dominant media has acted as an obstacle to true racial equality. In this essay, I attempt to breakdown this issue further, looking specifically at calls to Defund the Police in the years since the beginning of the Black Lives Matter movement.

International Perspective on Emerson and Douglass

By Braden Flax

Retracing the Abolitionist Imagination

A Bibliography by Ana Mariana Sotomayor Palomino